Sunday, March 30, 2014

Faces

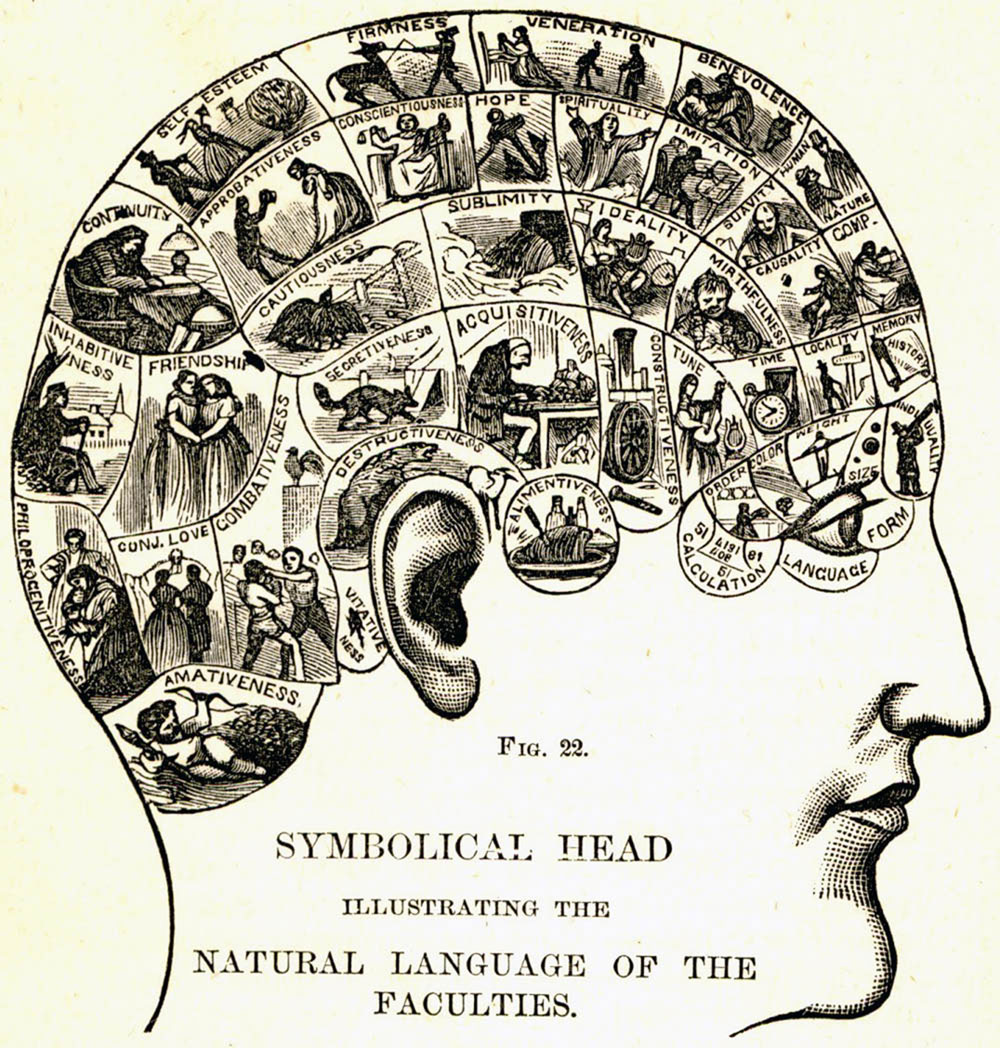

The thing I hate about the Internet is the same thing I hate about work: the social aspect. Work--even menial, wage-slave work--requires you to put on a face, to professionalize, to pretend. You don't just do a task, you play a role. You present yourself a certain way; you proclaim your investment in a project, goal, or career path. Ostensibly, your investments in these projects are real and your self-presentation, while not exactly real, isn't fake either. It's a different version of yourself: your professional self. Your work persona.

I don't mind it so much when I'm actually at work (or, at least, I recognize why it is appropriate or desirable in the same way that those fucking charcoal-colored "work trousers" are), but being asked to play that role outside of the office is going too far. "Networking and "professionalization" are the watchwords of my discipline and they've always struck me as particularly repellant ones. I especially hate "professionalize," which makes it seem like you become a professional in the same way that people in Greek myths turn into trees: I was mortal but then...I professionalized.

***

You get what you pay for. Likewise, if someone pays you, you have to give, even in ways you aren't prepared for. To work is to be a worker, to be a worker is to carry that burden into every aspect of your life. There is no self but the face you present, and the face you present is the one prescribed and approved by your boss. There it is: the crisis of permanent professionalization.

***

The Internet is where people self-promote: where they beg for money, where they "network," where they pretend to be ethically and politically engaged citizens by sharing articles about Miley Cyrus doing something that was Bad and Offensive. It's true that the Internet's role in our lives is a capacious one and includes private aspects (emails to loved ones, Google searches for "UTI after sex") as well as public ones, but the Internet is a space where performance and self-presentation are prioritized over interpretation. In real life, I "read" people as I perceive them (Who is this person? Are they a threat to me? What is their status in relation to mine?) instead of reading through their self-presentation. That doesn't mean that we are "natural" or completely unaffected when we're not online, only that I don't have to confront the people on the bus with interpretative skepticism. They exist, I exist. The fact that we have to look at each other is proof positive of that.

When we use the Internet to curate and present our best selves, what we're really doing is furthering a self-narrative of domination, in which I can command the attention of the person reading this because I am better and prettier and more famous. That is the flow of social media: the constant pulse of self-assertion which is always an assertion and never a request.

Tuesday, March 25, 2014

Stupid.

Last week, I had a meeting with someone I admire--"admire" in a partial, restricted sense, but admire nonetheless. Because I have so few opportunities to speak to people I don't hate, I found myself rehearsing what I would say in my head as I walked to meet him: They're wrong and they don't see why; they don't understand their own position, they don't see the logical end of it all and of course no one will ever stop them because people believe them; people will believe anything as long as it's stupid.

That last phrase ("people will believe anything as long as it's stupid") stopped me in my tracks. What could I have meant by that? The best way I can describe it is to say that it was a sort of mental slip-of-the-tongue: I hadn't actually meant to say (or think) it, although I'm not sure what I meant to say instead. It was an error with no possible correction, an originary mistake. People will believe anything as long as it's stupid. Once I said it, I believed it. Instantly and completely, I believed it.

But I didn't understand it. I could understand (and believe) variants of it: that people believe things which are stupid, that the dominant ideology is one of stupidity, or that the stupidity of an idea will not necessarily affect its reception. But the rule I had stumbled across was different: it posited that stupidity was the condition (or at least, a condition) for the acceptance of a given belief. It was right there in the phrase: people will believe x, provided that x is stupid.

***

Part of the problem is my own alienation, a growing sense that I don't identify with the categories used to describe me. I often feel that I won't be able to find common ground with other people about either politics or ethics unless we stick to the most generic observations possible: making children work is a factory is bad. I like feeling free and happy. It's terrible when people are sick.

But people will, inevitably, disagree, even about uncontroversial truisms like this. In fact, people will often justify blatant gaps in logic or incredible violence as long as it's a gap in their ideology or violence against someone they don't like. At the end of the day, that seems to be the purpose of ideology: a tool to avoid confronting your own failures.

***

***

Why? It doesn't make any sense. I know that. I recognize: it's stupid.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)